Gallery 3: Then and Now

The Museum is named after Richard, 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam (1745-1816), a graduate of Cambridge University with a passion for collecting. He felt strongly that the University should have its own museum, not only for the display of works of art, but also with its own library. In his will Fitzwilliam he left the princely sum of £100,000 (around £10,000,000 in today’s money) to build an unforgettable monument that would be both a place of learning and one of the most magnificent galleries of its day.

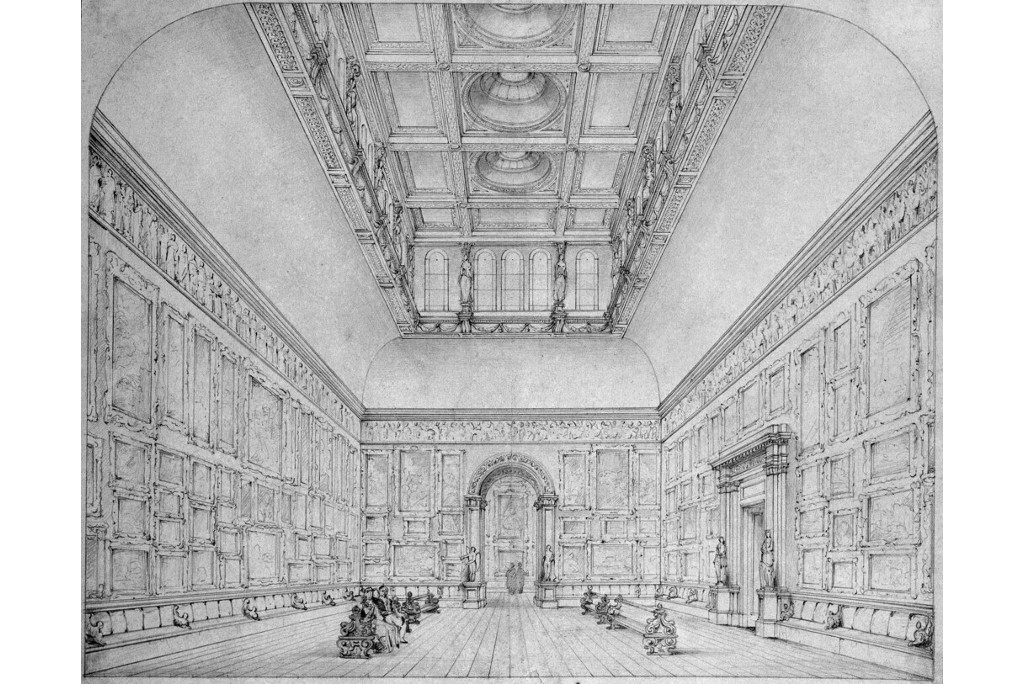

At the centre of the building, designed by the architect George Basevi (1794-1845) and completed by Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863), this gallery is widely considered one of the finest museum interiors in the world. Here, and throughout the museum’s galleries, paintings are hung alongside sculpture, furniture, ceramics, manuscripts and coins and medals in a distinctive installation that reflects the richness and diversity of the Fitzwilliam’s collections.

The frieze around the gallery is composed of plaster casts taken from the marble frieze of the Parthenon temple in Athens, built between 447 and 432 BC: its subject is a procession in honour of the goddess Athena. A large part of the original was removed from the temple by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, and can be seen today in the British Museum. The presence of these sculptures in Britain remains controversial.

The purchase of the ‘Parthenon Marbles’ for the British nation in 1816 transformed people’s understanding of Greek art, previously viewed through the medium of later Roman versions of Greek works.

George Basevi, twenty years old at the time and just embarking on his architectural career, would surely have been among the crowds flocking to view the Marbles in the British Museum. Competing to design the new Fitzwilliam Museum in 1835, he would also have been aware of the copy of the Parthenon frieze encircling the Athenaeum Club building in London, completed in 1830.

The frieze appears in one of Basevi’s earliest designs for this room. While clearly appropriate for a classically inspired building in a university where Classics was a principal subject of study, it has not met with universal approval: one critic in 1848, for example, strongly objected to ‘the junction of such coarse and mutilated figures with the rich and delicate adornment of the skylight’

The Parthenon frieze was about 160m long, the space available in this gallery is less than 60m. But the essential elements of the procession – the cavalcade of horsemen, the offering bearers, and the delivery of a special garment for the goddess – are all included.

Set high above eye level, as on the temple, two branches of the procession move in opposite directions to converge for the climax of the ritual, the handing over of the garment; this is centrally placed on the long wall opposite the doorway.